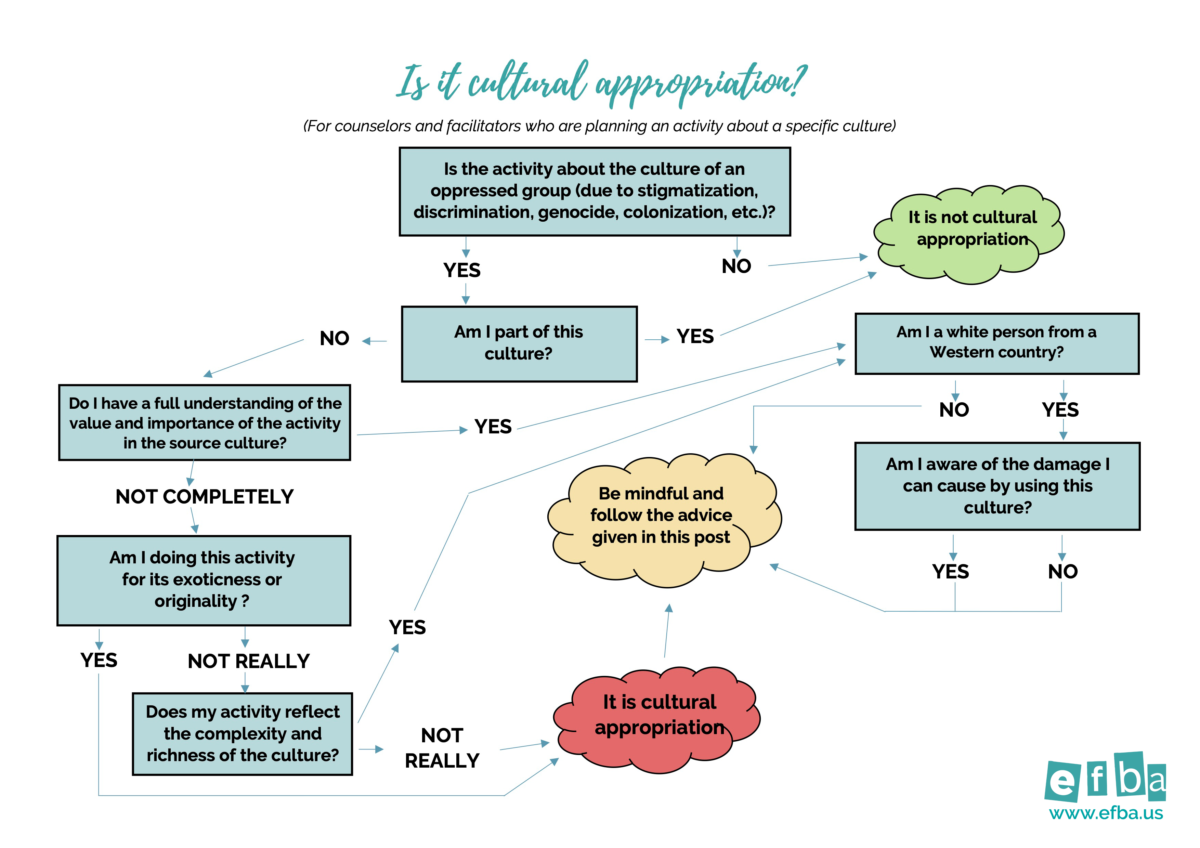

Whether it’s making a dreamcatcher, dressing up in a Native American headdress, or doing a “traditional African dance” workshop, camp leaders often have a hard time distinguishing between cultural appropriation, cultural appreciation, and cultural mixing. What is cultural appropriation? What damage does it perpetuate by conveying stereotypes that are detrimental to certain groups, often already discriminated against? Faced with these questions, which are more topical than ever, we at EFBA have decided to train our summer camp teams and teachers to make choices that respect each group and community. This article is here to explain our pedagogical position on cultural appropriation and to give camp counselors some practical advice to address cultural appropriation in summer camps.

What is Cultural Appropriation?

While the issue of appropriation has been debated for several years in the United States, and particularly in California, it is not always familiar to our foreign counselors and facilitators, especially across the Atlantic. But what is cultural appropriation?

The Office québécois de la langue française defines cultural appropriation as “the use, by a person or group of persons, of cultural elements belonging to another culture, generally a minority culture, in a way that is deemed offensive, abusive or inappropriate. By “cultural elements,” we mean all the codes, rituals, behaviors, symbols or images of a culture. In practice, we consider it cultural appropriation if:

- a cultural element is used in a context different from its original customary context;

- there is a power imbalance between the source culture and the culture in which the element is used;

- one has not been authorized by the source group to use their culture; and

- it causes harm.

Using a Cultural Element in a Context Different from its Original Context

One of the most emblematic cases of cultural appropriation is the use of Native American headdresses in costumes. More than a simple clothing accessory, they have a strong spiritual and social meaning and are only worn by men of the tribe who have earned the right to wear them. Wearing them as a costume without being from a Native American culture and without transmitting knowledge about them is denying their symbolism and the richness of the rites and cultures in question. The cultural appropriation is all the stronger since we are talking about a community marked by colonialism and genocide. It is the same for dreamcatchers or African masks.

Power Imbalance with the Source Culture

The notion of power is emphasized; in the case of cultural appropriation, a dominant culture appropriates elements from cultures that have been systematically oppressed. We can cite the example of Maori tattoos worn by Westerners. Debates on this topic have arisen in recent years. Opponents of the practice accuse the perpetrators: these tattoos were ridiculed when they were worn by the Maori (whose lands were stolen by European settlers), until the day when white people made them trendy. However, the tattoo is a ritual and ancestral art with strong symbolism. Many camp counselors have offered superficial workshops on Polynesia in which children painted shapes loosely based on those of the source culture, which was therefore mocked. These are some examples of cultural appropriation in summer camps.

How can we show appreciation for another culture?

If camp counselors really do want to pass on knowledge about another culture, what can they do to avoid cultural appropriation in summer camps? Here are several possibilities:

- Call on specialists (from an organization, museum, etc.);

- Involve a person from that culture (think of videoconferencing, which gives the possibility of making contact with thousands of communities around the world);

- Learn about the cultural element in depth to convey the most complete knowledge possible, taking advice from members of the community in question if possible and ensuring that they will not go against the rites through their activity. It is essential to ensure that the source group gives permission to use their culture.

If you are not able to do so, do not propose a theme dedicated to a culture that is in a power imbalance with respect to the so-called dominant culture.

Prejudice Against a Group

Made-in-China dreamcatchers harm the source culture not only because they do not respect their ancestral rites, but also because they make a mockery of the richness and complexity of Native American arts by passing them off as mere decorative objects. In addition, there is also a financial harm; the dominant group profits from the sale of these objects, without any benefit for the members of the source culture. Want to do a workshop related to Native American culture? Make sure to devote a budget to inviting a speaker or buying specific material from the group from which the culture originates.

In the United States, camps are often located on land historically owned by Native American tribes. Do some research: Who owned the land? How and when did the natives leave? Were treaties signed (and are they still honored)?

Remember that it is essential to reflect the complexity and richness of cultures in what you explain to children. You cannot offer a “traditional African dance” workshop, which would be as absurd as offering a “traditional European dance” workshop and erase the richness and diversity of different cultures. When you suggest that children make an object historically used by indigenous peoples, the object created must faithfully reflect the complexity of the techniques and pay tribute to a heritage. A rain stick made from a roll of paper towels, aluminum and rice is not a rain stick.

As a general rule, counselors should be particularly careful not to reuse a community’s culture as a joke (wearing a Chinese hat and using a weird accent, or wearing a Native American headdress and speaking with a limited vocabulary are things that can be regularly observed at camp). More broadly, take care not to perpetuate stereotypes, which, even if they are often appreciated by children, lock the targeted group into a dominated position. There are countless scenes of a male counselor disguising himself as a woman, sexualizing or dumbing her down. What vision will the little girl who witnesses the scene have of herself while growing up? The same is true when a male counselor plays a Portuguese man who is confined to housework. Faced with this recurring stereotype in France, a child of Portuguese origin risks internalizing the fact that they are not legitimate in positions of power.

It is very likely that you have been confronted with racist situations or jokes in the past, and may not even have been able to understand why they were inappropriate. Consider the fact that society is rapidly changing on these issues. Racist jokes that made people laugh ten years ago would probably cause an uproar today, and that’s good. Blackface and yellowface, the practice of painting one’s face black or yellow to “dress up” as Black or Asian people, have been used many times by white people to caricature them and are now considered particularly offensive. As educators, we can teach children that we don’t need to ridicule or belittle a person or a group in order to laugh and have a good time, and that in escaping, we can discover other people’s cultures for real!

Turn your nose up at stereotypes by reversing the roles in your dramatizations, in the choice of historical figures you present, in the books you make available to children. Groups that are usually discriminated against can also be the saviors, leaders, scientists, experts, and heroes of your stories!

Cultural Exchange or Appropriation?

Many white people are indignant when criticized for their dreadlocks or Maori tattoos. They then interpret these criticisms as a check on what they can and cannot do, when for them it is only a question of personal choice, expression, or interest in other cultures.

And then there are people who see cultural appropriation everywhere, even in the practice of yoga or the consumption of tea. According to them, why only criticize celebrities who wear dreadlocks when a large part of the white population regularly eats sushi (with chopsticks to boot)?

So, where is the line between cultural exchange and cultural appropriation?

Cultural exchange is built on common ground, where there is no dominant-dominated relationship, unlike cultural appropriation.

Are so-called minority cultures equal vis-à-vis majority cultures? Take a moment to think about it: coming to work with dreadlocks, sarouel pants or a sombrero is often frowned upon and considered unprofessional, and some languages remain under-valued (for example, it is rare in France to hear a counselor congratulate a child on their mastery of Arabic or Bambara). At the same time, a person from a marginalized culture is often forced to put aside their cultural practices in order to survive (find and keep a job, obtain a position of power, socially assimilate, etc.). As a result, the relationship between majority cultures, which appropriate cultural elements from the very people they stigmatize and marginalize, and minority cultures is unequal.

As educational counselors, drive change by being intentional in your choices. Every story you decide to tell, every character you play, every song, activity, theme, or setting must have been selected for conscious and deliberate reasons. If you want to deepen understanding of a historically and systematically oppressed culture, call on expert speakers from that culture. Promote multiculturalism among children, fight against stereotypes, and learn about the historical context of cultural borrowing, the power relations between different groups, and the possible consequences of cultural appropriation in summer camps. It’s in your hands!

By Julia Peillon

Resources for Further Reading:

Learn more about the harms of cultural appropriation in summer camps.

ONLINE ARTICLES

(French) Interview with sociologist Eric Fassin on the concept of cultural appropriation (Le Monde article)

VIDEOS

(French) YouTube artist Naya Ali defines cultural appropriation and differentiates it from cultural appreciation.

(French) The concept of cultural appropriation sounds complicated. But at the end of the day, it’s just a matter of (bullies’) sensibilities.

(French) Quebec program Corse sensible discusses the cultural appropriation of Indigenous art

(English) Cultural Appropriation vs. Appreciation (by the CBC YouTube channel)

TOOLS

(English) Everyday Discrimination Scale (Harvard University article)